Diophantus: the Ancient Mathematician and his Riddle

Diophantus isn’t a household name, but his fingerprints sit quietly all over modern algebra. Only fragments of his work survived, yet they read like messages from an ancient mind trying to invent the very language numbers now speak.

A Mathematician Lost in the Cracks of Time

Most ancient thinkers left statues, myths, or fan clubs. Diophantus left algebra problems — cryptic, clever, and strangely modern. His surviving texts suggest a mathematician who wasn’t content with the clunky arithmetic of his day; he wanted a smoother, symbolic shorthand for thought. And he took steps toward creating it centuries before anyone else tried.

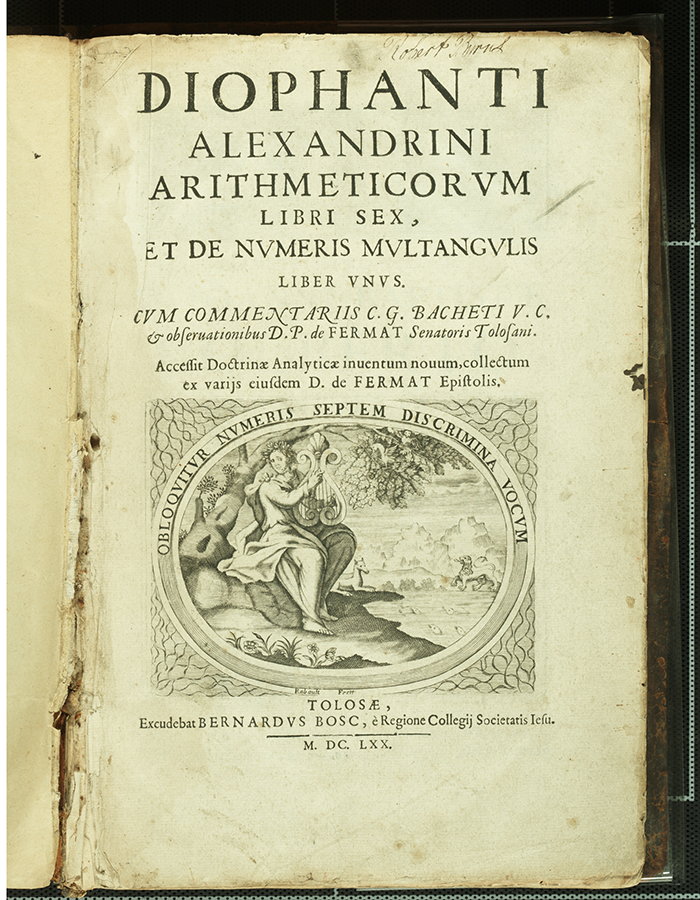

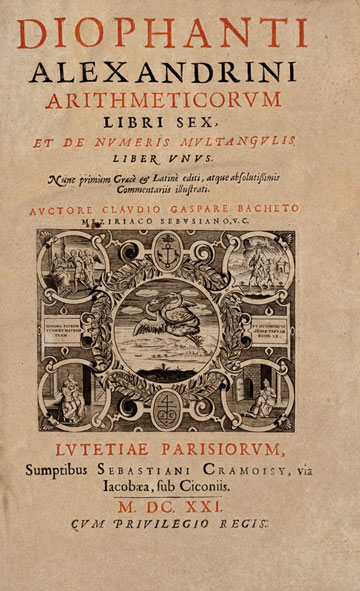

Only six of the original thirteen books of Arithmetica made it out alive, a reminder that history often survives by accident rather than intention. But those six are enough to reveal a mind carving symbols out of chaos, pushing mathematics away from long sentences and toward compact notation. In the ruins of ancient scholarship, his work still glows.

Diophantus wrote algebra like he was trying to future-proof it — and in fragments, he modernized algebra. #AncientScience #Algebra share this

The Birth of Algebra’s Secret Handshake

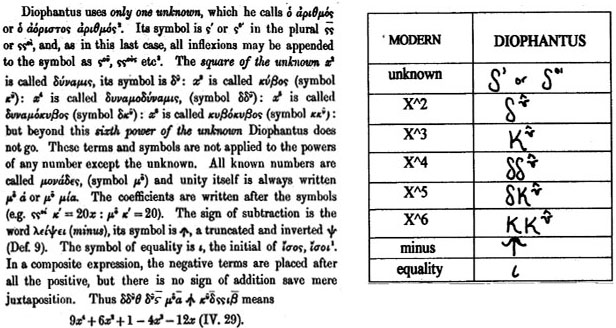

Before Diophantus, mathematical writing was basically prose — perfectly fine for philosophy, less ideal for anything with variables. So he began using symbols for operations, abbreviations for unknowns, and stripped-down expressions. It wasn’t the algebra we know, but it was a prototype of the way mathematicians think. A quiet revolution written in Greek squiggles.

His innovations weren’t flashy. They were practical, almost sly, like someone shaving seconds off a tedious task. By substituting symbols for numbers and operations, he gave mathematics a toolkit to compress ideas, making problems easier to express — and harder to misinterpret. Even today, researchers studying Arithmetica can feel the shift toward abstraction beginning.

When Diophantus swapped long phrases for symbols, he didn’t just simplify math — he changed its destiny. #MathHistory share this

His claim to fame comes from substituting symbols for numbers and operations in equations, thus creating algebra, but everything else we know about his life comes from a single algebraic riddle.

Here it is:

“Here lies Diophantus.

God gave him his boyhood one-sixth of his life;

One twelfth more as youth while whiskers grew rife;

And then yet one-seventh ‘ere marriage begun.

In five years there came a bouncing new son;

Alas, the dear child of master and sage,

After attaining half the measure of his father’s life, chill fate took him.

After consoling his fate by the science of numbers for four years, he ended his life.”

For those keeping score, that means

x/6 + x/12 + x/7 + 5 + x/2 + 4 = x

Obviously, x equals the number of years Diophantus lived. This equation also assumes that Diophantus’ son died at an age equal to half his father’s ultimateage (transcribed in the equation above, in bold, as “x/2”), as opposed to Diophantus’ age at the time of his son’s death.

Simplifying the equation gives us:

25x/28 + 9 = x

Which we can clean up in a few steps:

25x = (x-9) x 28

25x = 28x – 252

3x = 252

x = 84

And that means Diophantes died at 84.

This “biography”, if you will, was first written down in the Greek Anthology, compiled by Metrodorus around 500 AD. It may not be wholly accurate, but it is fun.

Problems as Messages Across Millennia

Diophantus didn’t just theorize; he demonstrated. Arithmetica is loaded with problems designed to teach by example — riddles, really, each showcasing how his symbolic toolkit solved equations. His puzzles read like ancient brain teasers that accidentally helped define algebraic reasoning.

What makes the work surprising is its tone: not mystical, not lofty, just precise and practical. He solved equations the way a modern student might: step-by-step, substitution, transformation, solution. The style feels familiar because it became the foundation of the discipline. Across centuries, his voice reads like someone who assumed his ideas would matter later.

Diophantus’ ancient math problems feel modern — like he knew we’d eventually show up to read them. #Neurodope share this

Survival by Fragment, Influence by Echo

We only have six of thirteen books, and that missing seven gnaws at historians like lost chapters of a codebook. Even so, the surviving pieces influenced Islamic algebraists, Renaissance mathematicians, and eventually Fermat — the guy famous for scribbling impossible notes in margins. Diophantus became a ghost mentor to centuries of mathematicicians.

The irony is thick: the man who helped structure algebra lives mostly through absence. His influence echoes louder than his biography, his problems louder than his persona. All we truly know is the work — but the work is enough. It shows a mathematician quietly bending numbers toward the future.

Half his books vanished, but Diophantus still shaped algebra. Sometimes the fragments outlive the whole. #AncientGenius share this

A quick overview of the topics covered in this article.

How do ya like my little magazine? Neurodope Magazine is a sardonic, science-meets-philosophy publication that explores the strange, the curious, and the mind-bending corners of reality with wit, skepticism, and insight.

If this kind of brain static hits your frequency, subscribe for articles to your inbox. I try to look deeper into things and write about them: commentary on society, science, and space.. After all, there's a whole lot of unknown unknowns out there.. and I'm curious to the ideas surrounding them. Thanks for reading! - Chip

Latest articles

“The truth is rarely pure and never simple.” – Oscar Wilde

“The truth is rarely pure and never simple.” – Oscar Wilde

“There is no place in a fanatic’s head where reason can enter.” – Napoleon Bonaparte

"There is no place in a fanatic's head where reason can enter." - Napoleon Bonaparte

“Science is the great antidote to the poison of enthusiasm and superstition.” – Adam Smith

"Science is the great antidote to the poison of enthusiasm and superstition." - Adam Smith