On Being Conscious to Yourself

Most philosophers know that “conscious” comes from Latin and entered English via John Locke. But the deeper story, tracing all the way to Greek, reveals a paradox at the heart of awareness. The word’s origins suggest consciousness is less an internal spotlight and more a shared conversation—even when that conversation is with oneself. Douglas Hofstadter might call this a “strange loop,” but the etymology tells us it was baked into the very word.

Latin Roots: Knowledge Together

The English “conscious” comes from Latin conscius, itself derived from con- (“together”) + scire (“to know”). In Latin usage, conscius meant knowing with someone else—a relational concept. Knowledge wasn’t something contained solely in one mind but shared among individuals. C.S. Lewis notes that conscius implied an interpersonal awareness, a sort of social knowing, long before “consciousness” became a personal state.

Yet the story gets more intriguing: conscius could be reflexive. Phrases like conscius sibi, literally “knowing with oneself,” appear frequently in Latin literature. Translators rendered these as “conscious to oneself,” a figurative usage signaling self-awareness—knowing that one knows. The Latin phrase sets the stage for the modern concept of reflexive consciousness, a linguistic artifact of humans talking to themselves.

Consciousness started as chatting with others. Somehow it turned inward. #EtymologyOfConsciousness #StrangeLoop #KnowYourself share this

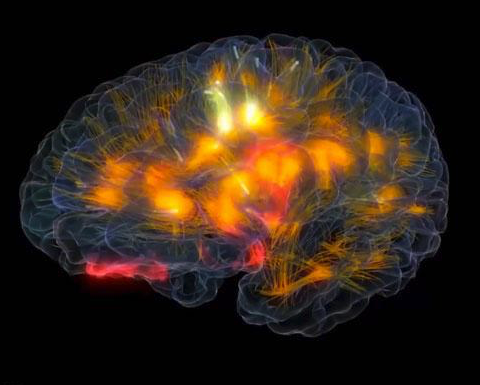

Your brain lights up when predictions come true. Ideology knows this.

Greek Beginnings and Early English Adoption

Going further back, conscius comes from the Greek syneidesis, used as early as the 5th century B.C. in the Bible, usually translated as “conscience.” Syneidesis, like conscius, could be reflexive, describing knowledge shared with oneself—synoida emautoi. This paradoxical idea mirrors the internal dialogue we all experience, the sense that thinking is a conversation with an internal other, speaker and listener in one brain.

When “conscious” first entered English in the 1500s, literate audiences understood the Latin meaning of shared knowledge. Early texts still framed consciousness relationally. Hobbes wrote of knowledge shared between people, and Bishop South equated being conscious with being fully aware in friendship. The reflexive sense—“conscious to oneself”—appeared around 1600 and persisted in theological and poetic works for more than a century.

We’ve been talking to ourselves for centuries. Language just made it official. #ConsciousToOneself #HistoricalEtymology #StrangeLoops share this

The human brain: a web of neural fire shaping our reality and awareness.

From Reflexive Latin to Locke’s Consciousness

Over time, “conscious to oneself” became simply “conscious.” By the late 1600s, the “to oneself” part felt redundant, and the word was understood as self-aware knowledge. Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding codified the modern meaning: consciousness as perception of one’s own mental processes. Later philosophers, like Clarke and Reid, expanded on this, describing immediate knowledge of thoughts and actions.

Thus, the modern notion of consciousness evolved from a Latin phrase about relational knowing, through reflexive constructs, into the individualized mental awareness we use today. In other words, “conscious” didn’t start as awareness—it started as communication, sometimes with oneself, sometimes with others, and ultimately, with the mind’s strange loop reflecting on itself.

Consciousness began as a chat with others, ended as a chat with yourself. #Etymology #Consciousness #StrangeLoop share this

Brain antomy, 19th century artwork. Artwork from the 1886 ninth edition of Moses and Geology (Samuel Kinns, London). This book was originally published in 1882.

The study of consciousness etymology reveals how language shapes thought. From Greek syneidesis to Latin conscius to English “conscious,” the evolution demonstrates a shift from social knowledge to introspective awareness. Reflexive forms like conscius sibi show the early awareness of metacognition—the ability to observe and communicate with oneself. Cognitive science today recognizes this loop in neural and linguistic processes, where internal dialogue structures thought and identity. The historical record—from Hobbes to Locke—illustrates the gradual internalization of shared knowledge into personal awareness, offering insight into both philosophy and psychology.

References:

Consciousness: Etymology and History

Strange Loops and Self-Knowledge

Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding

A quick overview of the topics covered in this article.

Latest articles

The Cognitive Rent Economy: How Every App Is Leasing Your Attention Back to You

You don’t lose your attention anymore. You lease it. Modern platforms don’t steal focus. They monetize it, slice it into intervals, and return it [read more...]

AI Is an Opinionated Mirror: What Artificial Intelligence Thinks Consciousness Is

Artificial intelligence thinks it sees us clearly. It does not. It is staring into a funhouse mirror we built out of math, bias, hunger [read more...]

The Age of the Aeronauts: Early Ballon flights

Humans have always wanted to rise above the ground and watch the world shrink beneath them without paying a boarding fee or following traffic [read more...]

Free Energy from the Ether – from Egypt to Tesla

Humans have always chased power from the invisible. From the temples of Egypt to Tesla’s lab in Colorado, inventors sought energy not trapped in [read more...]

The Philosophy of Fake Reality: When Simulation Theory Meets Neuroscience

What if reality isn’t breaking down—but revealing its compression algorithm? Neuroscience doesn’t prove we live in a simulation, but does it show the brain [read more...]

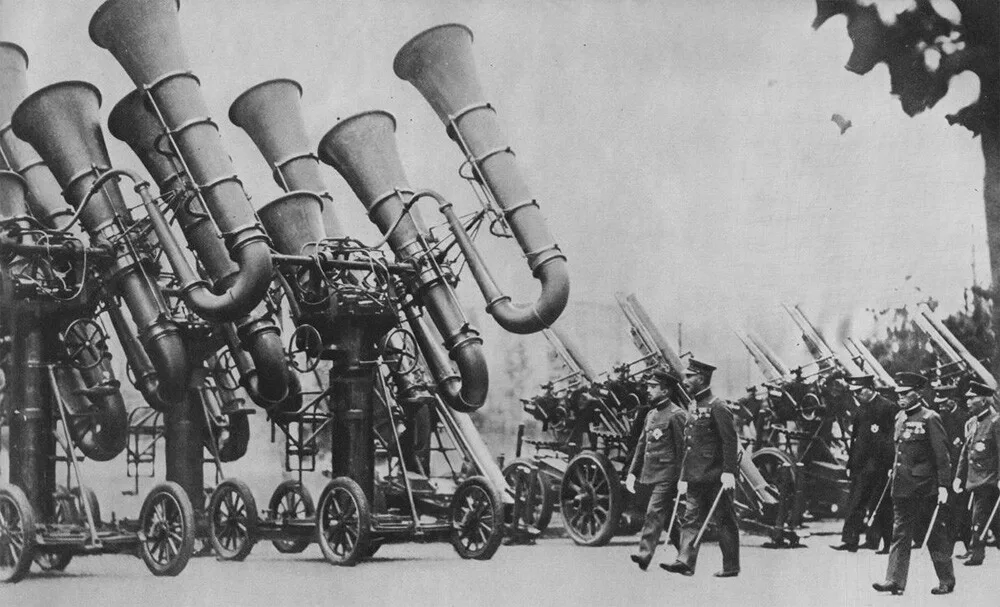

Blast from the Past: Exploring War Tubas – The Sound Locators of Yesteryears

When it comes to innovation in warfare, we often think of advanced technologies like radar, drones, and stealth bombers. However, there was a time [read more...]

Pneumatic Tube Trains – a Lost Antiquitech

Before electrified rails and billion-dollar transit fantasies, cities flirted with a quieter idea: sealed tunnels, air pressure, and human cargo. Pneumatic tube trains weren’t [read more...]

Tartaria and the Soft Reset: The Case for a Quiet Historical Overwrite

Civilizations don’t always collapse with explosions and monuments toppling. Sometimes they dissolve through paperwork, renamed concepts, and smoother stories. Tartaria isn’t a lost empire [read more...]

“A problem cannot be solved by the same consciousness that created it.” – Albert Einstein

“A problem cannot be solved by the same consciousness that created it.” - Albert Einstein

Tartaria: What the Maps Remember

History likes to pretend it has perfect recall, but old maps keep whispering otherwise. Somewhere between the ink stains and the borderlines, a ghost [read more...]