Tartaria: What the Maps Remember

History likes to pretend it has perfect recall, but old maps keep whispering otherwise. Somewhere between the ink stains and the borderlines, a ghost empire flickers: not quite erased, not quite acknowledged, just waiting for someone to ask why it was ever there at all.

The Cartographer’s Freudian Slip

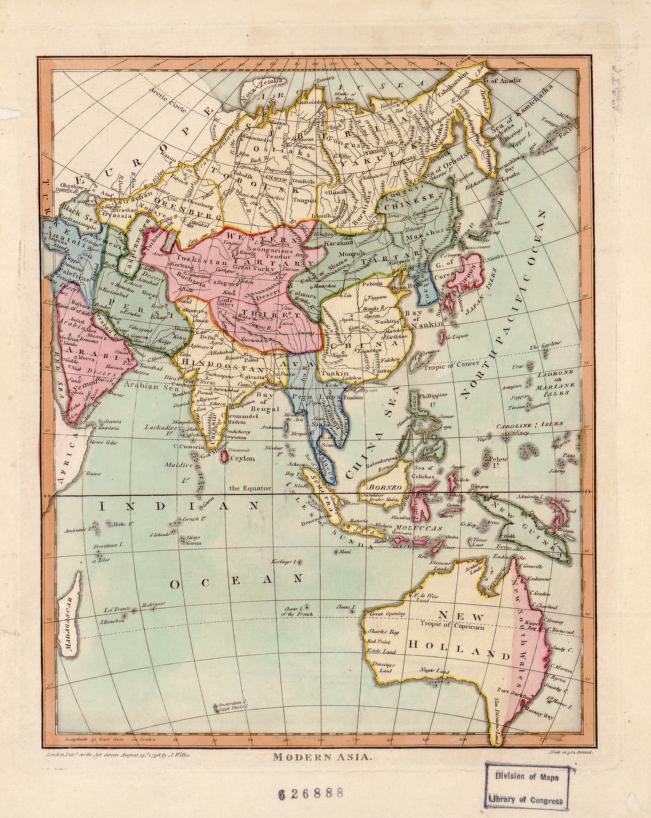

Early atlas makers didn’t hesitate; they inked “Tartary” across half of Eurasia like it was a fact of nature. A landmass-sized shrug, a casual territorial monolith, a continental identity written with the confidence of someone naming a mountain range. Yet the textbooks act like it was a clerical accident, a typo that somehow lasted centuries. But maps don’t hallucinate at scale. They record whatever the people of their day treated as known, real, inherited. And the sheer ease with which “Tartary” stretched across the steppe suggests an entity, political, cultural, or civilizational that was understood well enough not to require explanation.

Dig long enough and you find the problem: the deeper you go into early charts, the more fluid the lines become. The cartographers weren’t drawing borders; they were sketching memory. Their pens caught the edges of a world that had already begun dissolving. “Tartary” was less a kingdom than a placeholder, a word-shaped fossil of something too big, too decentralized, or too mythic to survive the cleanup pass of modern nation-building.

Old maps don’t lose civilizations. They leave the lights on for whoever remembers to look. share this

The Empire That Vanished Quietly

If Tartary were nothing, it should have vanished loudly. Scholars should argue over the ashes. Empires don’t evaporate without bureaucracy: no wars of dissolution, no treaties, no cradle-to-grave chronicles. Yet Tartary slips out of recorded history like a tide draining from a beach, swift, silent, unacknowledged. Something that big shouldn’t die unnoticed. Unless the noticing was the part that was edited out.

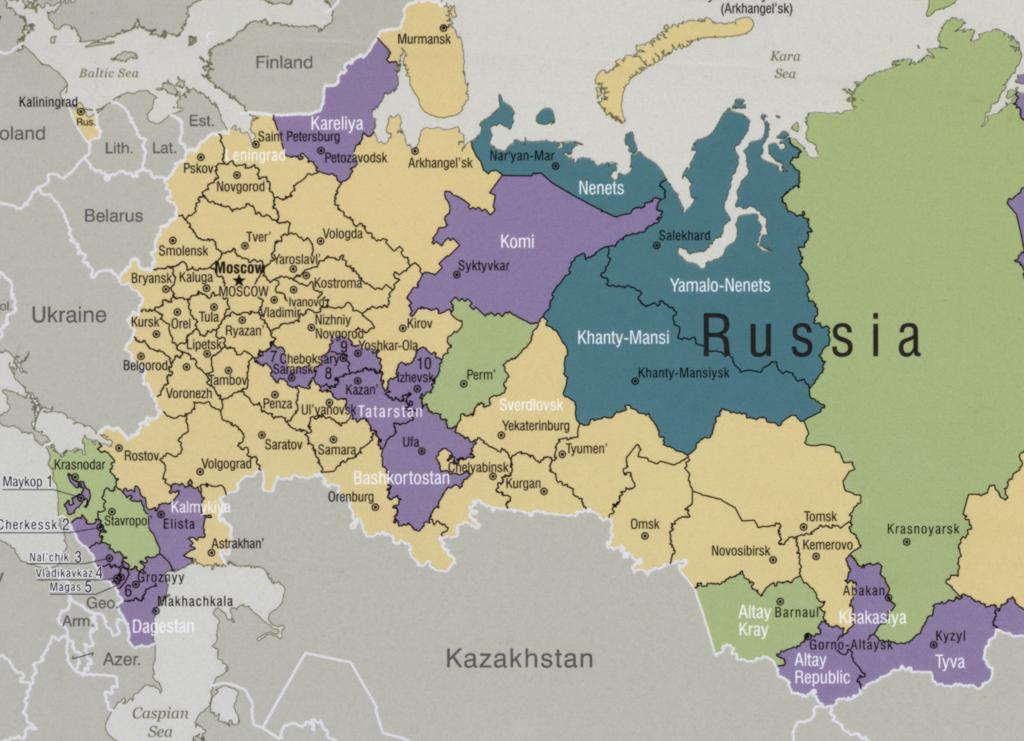

Historical erasure isn’t always malicious. Sometimes it’s strategic. Sometimes it’s administrative. Sometimes it’s the victors cleaning up their paperwork. When Russia expands eastward, when China codifies its dynastic borders, when Europe redraws its idea of “civilization,” Tartary becomes the thing that no longer fits, a concept filed away under “miscellaneous” until the category itself is deleted. And what does the modern mind do with unexplained leftovers? It forgets.

Civilizations don’t vanish. We just rename them until we forget they were ever real. share this

Ink Layers Over Consciousness Layers

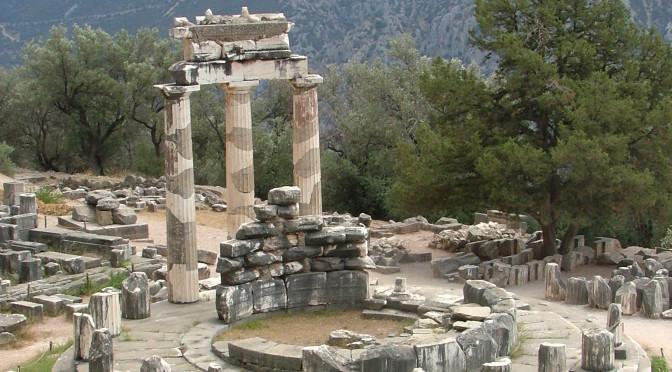

Every map is a confession. Not just of geography, but of worldview of who mattered, who didn’t, who was visible, who was flattened. Tartary sits in that liminal zone where fact and myth have equal claim. Its borders shift not because the land changed, but because the perception of power changed.

The maps remember what the historians don’t want to account for: a cultural zone that defies the neat narrative arcs of nation-state logic. So what if maps also served a purpose to label unknown concepts of living? Describing what can’t be described on their map.

What if old maps function like palimpsests? Layers of consciousness piled on each other. In other words, the remembered, the half-remembered, the overwritten. “Tartary” lingers as the ghost text, the underlayer, the faint scrawl the modern world wrote over but couldn’t quite kill. When you peel back the academic gloss, the old cartography still carries that earlier thought-form: a vast, cohesive cultural identity too large to compress into one modern nation.

Or maybe too inconvenient.

Erase the story all you want: the map still remembers the shape of the forgotten world. share this

The Linguistic Breadcrumb Trail of Tartaria

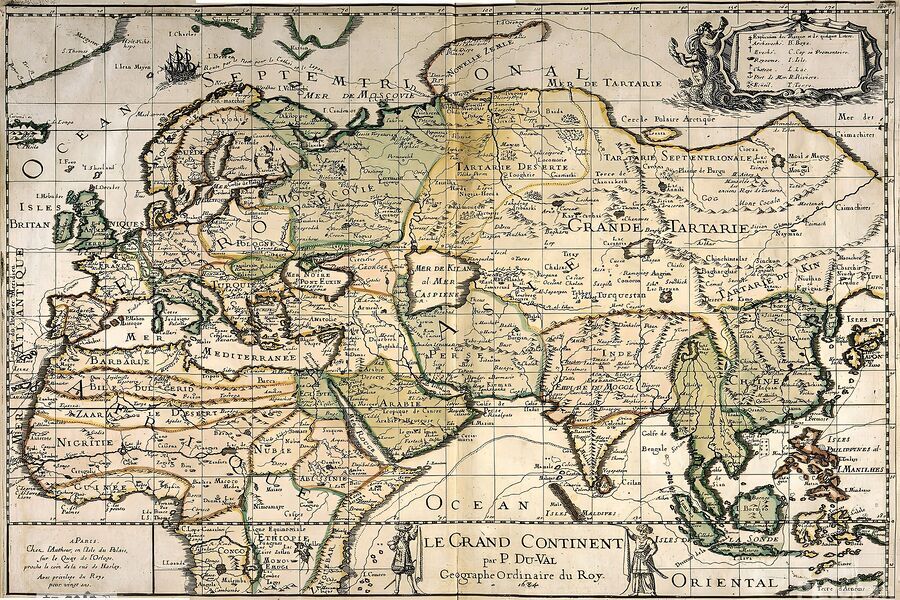

Look at the names: Tartary, Grand Tartary, Independent Tartars, Chinese Tartary, Mogul Tartary. A taxonomy of something that supposedly never existed. Language doesn’t multiply categories for non-entities. The sheer variety suggests regional distinctions inside a conceptual whole, like a federation, a diaspora, a civilizational sphere whose internal differences were noted but whose overarching identity was recognized by all mapmakers of the time.

Even stranger: echoes of the word survive in folklore, in place names, in ethnonyms that academic history treats like linguistic rubble. But linguistic rubble only exists when a structure has collapsed. Something stood there once. Something large enough to leave its linguistic fingerprints across continents. When those fingerprints don’t match any recognized narrative, academia shrugs. Neurodope Magazine follows the trail.

Words are fossils. And ‘Tartary’ is a bone from something massive we’re not supposed to reconstruct. share this

Layers of Ink, Layers of Memory

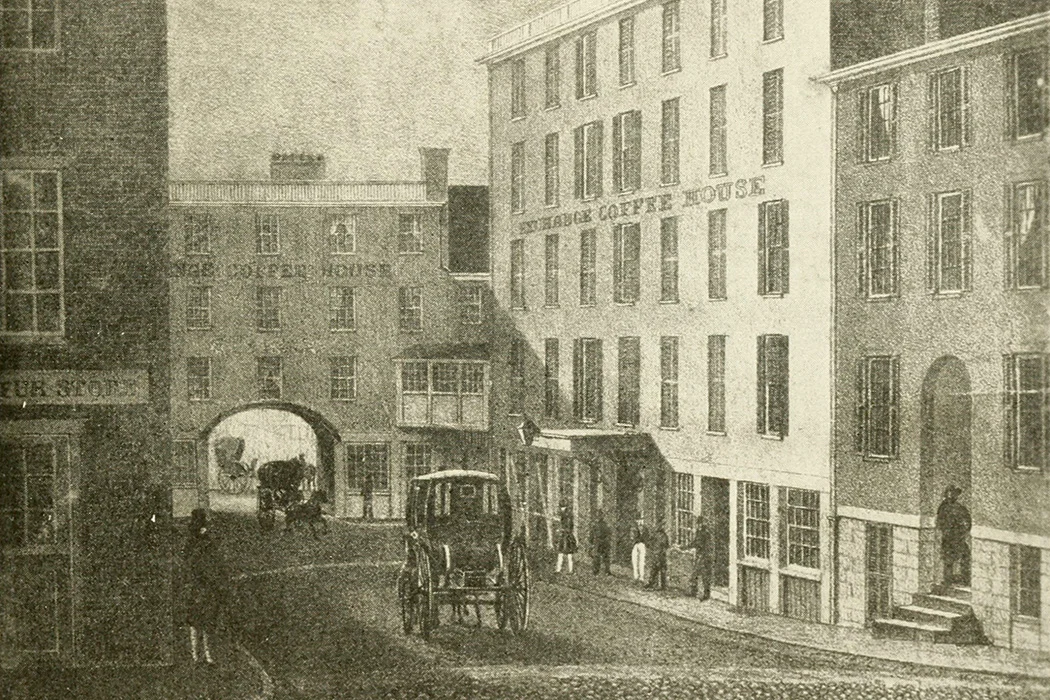

Not all ghosts whisper in legend. Some whisper in ink. The Library of Congress recently walked through a fascinating trail of old Western maps where “Tartary” or its Latin cousin Tartaria – pops up from the 13th through the 19th centuries as a label, an idea, a place-name bigger than any modern nation. What’s curious is not just that the label exists – but how casually it appears, how inconsistently it moves, and how it recedes entirely from modern mapping.

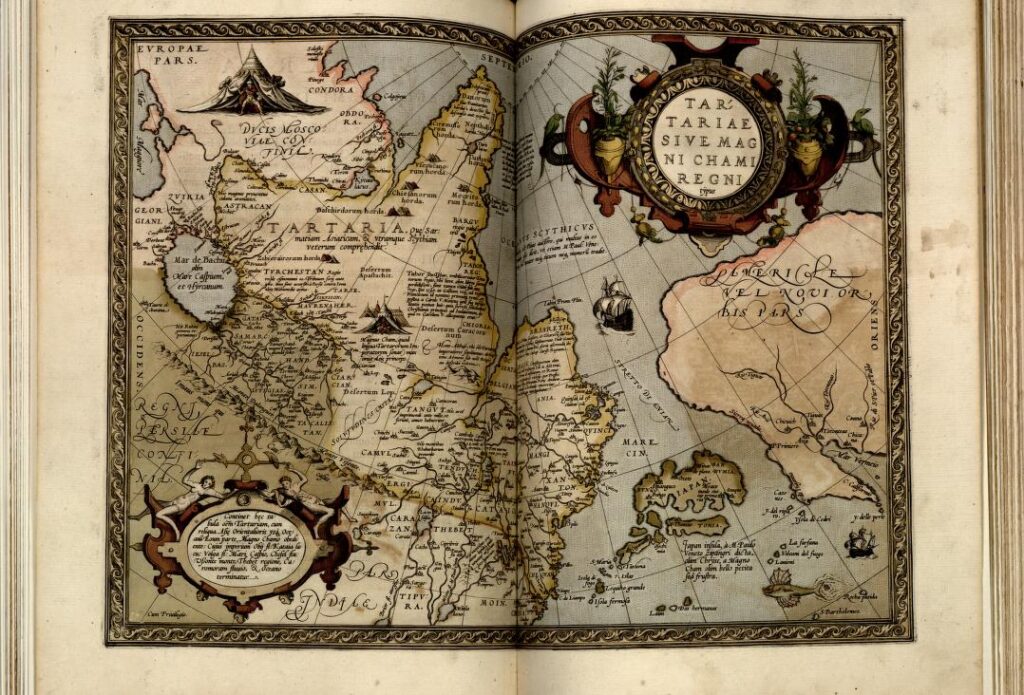

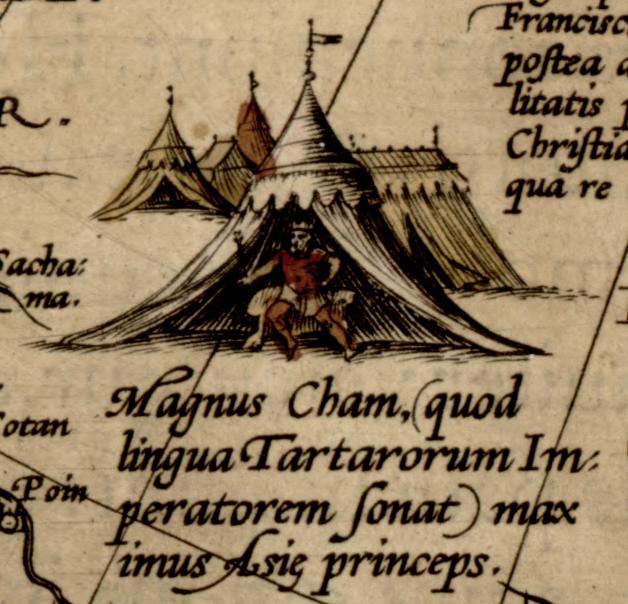

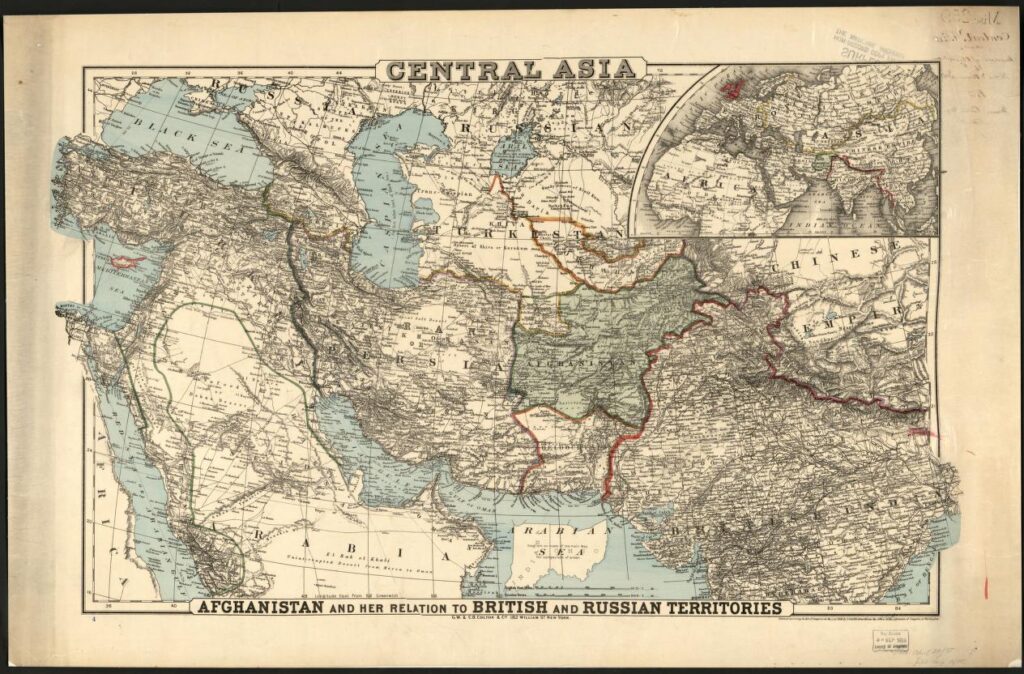

From medieval charts where Asia is an unknown sprawl to Renaissance atlases where Tartaria sprawls from the Volga River to the Pacific Ocean, the word has presence. In a 1570 atlas by Abraham Ortelius, the label Tartariae sive magni Chami regni – “Tartary or the kingdom of the great Cham” – bridges continents, mountains, deserts, and oceans without hesitation. That kind of expansiveness is not ignorance; it’s recognition at scale.

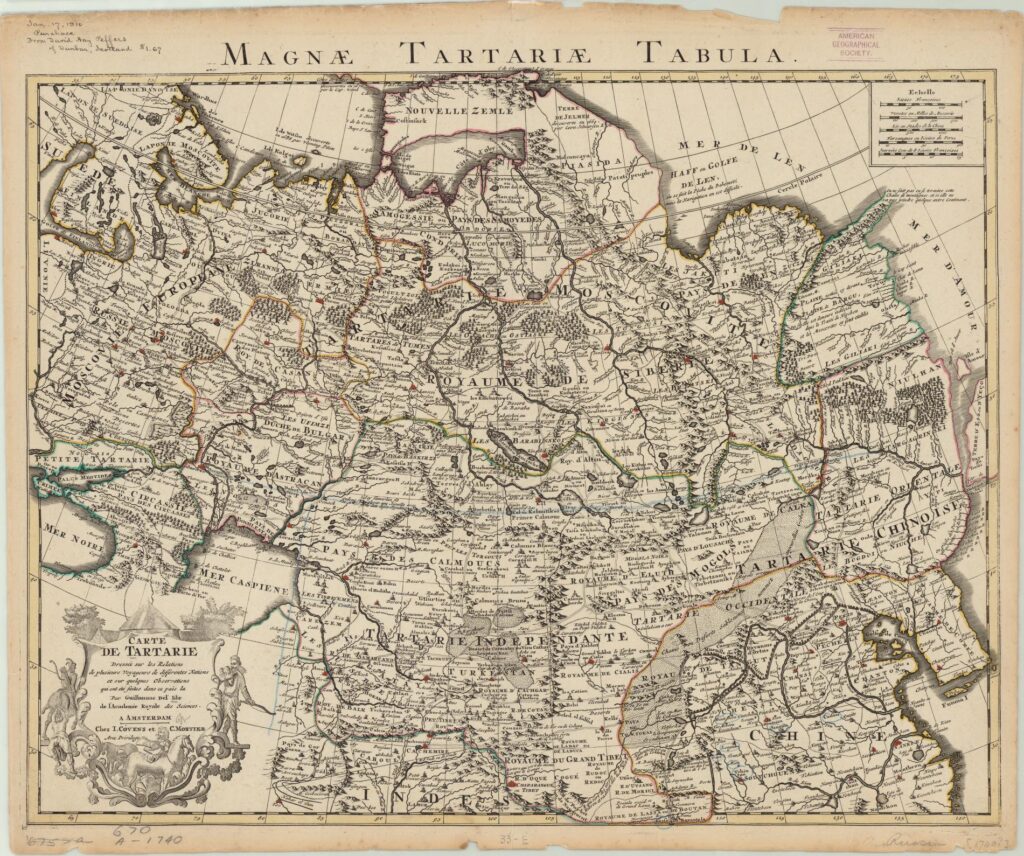

But here’s the twist: by the time detailed cartography arrives in the 18th and 19th centuries, the label hasn’t solidified as a political or cultural entity. Instead it splinters into modifiers: Western Tartary, Chinese Tartary, Independent Tartary, even narrower labels like Muscovite Tartary and Tartars of Dagestan, as though the name itself is an old code being tagged to whatever regional information the mapmaker has on hand.

Old maps don’t just draw borders, they encode forgotten geographies and vanished worldviews. share this

The Etymological Signal in the Noise

The very word Tartary is a fossil. Originally a Latinized form pointing to the land of the Tatars, it was reshaped by European scholars who linked it — partly by accident, partly by analogy, to Tartarus, the Greek netherworld. That extra “r” wasn’t just a spelling drift; it was a conceptual shift. What began as an ethnonym became a placeholder for the vast and unknown steppes beyond Europe’s gaze, a name stamped on space that wasn’t quite understood but needed naming anyway. The Library of Congress

The ethnographic reality was complex. “Tatars” referred to a broad set of Turkic and Mongolic groups with shifting alliances and identities across Eurasia — peoples with deep histories, not single-title empires. Yet map after map carries the label Tartary across terrains that included Manchus, Mongols, Tibetans, Siberians, and countless others. In a sense, Tartary became a linguistic catch-all, a global wild card written into Western cartographic consciousness.

Here we ask: what if Tartary wasn’t meant to be tidy? What if it was a collective name for a civilizational flux that didn’t fit the border logic of later nation-states? The name’s persistence…despite its vagueness…suggests it carried meaning and memory even where modern history has left a silence.

Tartary wasn’t a mistake: it was a placeholder for the indescribable. share this

Shifting Shapes Across Centuries

Mapmaking isn’t just a science; it’s an act of cultural cognition the way one era sees the world and what it chooses to highlight. In early atlas editions, Tartary dominates vast swaths from the Caspian to the Pacific, even as the mapmaker admits to questionable coastlines and borders that dissolve into rough sketches. Yet centuries later, the name fragments. Regions once undivided bear other titles: Siberia, Turkestan, Manchuria, Mongolia. The old label recedes, replaced by the political lexicon of empires growing their bureaucratic shadows.

There’s an archival poetry in that fade. As exploration deepened and sources multiplied, mapmakers didn’t erase Tartary so much as refine it, breaking it up, partitioning it, aligning it with emerging political entities. That’s not disappearance: it’s transformation. It’s a shift from something vast and conceptually unified to a mosaic of named regions once again too complex for a single label.

And then the word stops showing up. By the late 19th century, European and American atlases substitute Tartary with categories that fit the age of empires and nation states. The old maps still exist; the language remains in archival repositories. But the term itself has sloughed off: a ghost name in a layer beneath the visible text of history.

By the 19th century, Tartary vanished from maps but its ghost remains in the circuits of cartographic memory. share this

Cartography as Consciousness, Not Just Geography

At the Library of Congress, Tartary becomes a case study in the evolution of mapmaking: how names travel, mutate, split, and disappear; how explorers, storytellers, and atlas editors collaborate to define the unknown. But Neurodope Magazine asks a deeper question:

Is this pattern of naming and renaming merely a byproduct of better surveying — or is it an echo of a once-shared framework of understanding that our modern grids have overwritten?

Look closely at the sequences: a unified vast name → regional modifiers → disappearance. It’s almost as if the word Tartary was a lens through which Western cartographic consciousness viewed a world it couldn’t yet understand or measure — a cognitive placeholder for complexity, diversity, and scale that only later epochs would try to subdivide and tame.

In that sense, Tartary wasn’t just a map label. It was a world-model, maybe a conceptual field before the age of precision. When we draw our contemporary borders without it, we aren’t just updating cartography; we’re overwriting a layer of human perception that once saw something different. The Library of Congress

Maps remember what rulers rewrite. Sometimes the names that vanish tell us more than the names that stay. share this

A quick overview of the topics covered in this article.

Latest articles

The Cognitive Rent Economy: How Every App Is Leasing Your Attention Back to You

You don’t lose your attention anymore. You lease it. Modern platforms don’t steal focus. They monetize it, slice it into intervals, and return it [read more...]

AI Is an Opinionated Mirror: What Artificial Intelligence Thinks Consciousness Is

Artificial intelligence thinks it sees us clearly. It does not. It is staring into a funhouse mirror we built out of math, bias, hunger [read more...]

The Age of the Aeronauts: Early Ballon flights

Humans have always wanted to rise above the ground and watch the world shrink beneath them without paying a boarding fee or following traffic [read more...]

Free Energy from the Ether – from Egypt to Tesla

Humans have always chased power from the invisible. From the temples of Egypt to Tesla’s lab in Colorado, inventors sought energy not trapped in [read more...]

The Philosophy of Fake Reality: When Simulation Theory Meets Neuroscience

What if reality isn’t breaking down—but revealing its compression algorithm? Neuroscience doesn’t prove we live in a simulation, but does it show the brain [read more...]

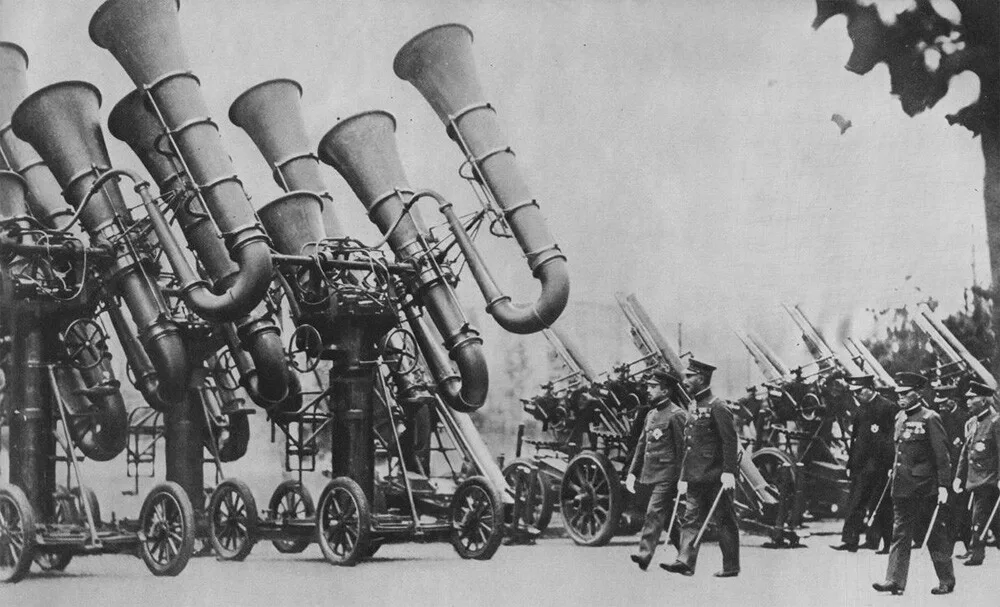

Blast from the Past: Exploring War Tubas – The Sound Locators of Yesteryears

When it comes to innovation in warfare, we often think of advanced technologies like radar, drones, and stealth bombers. However, there was a time [read more...]

Pneumatic Tube Trains – a Lost Antiquitech

Before electrified rails and billion-dollar transit fantasies, cities flirted with a quieter idea: sealed tunnels, air pressure, and human cargo. Pneumatic tube trains weren’t [read more...]

Tartaria and the Soft Reset: The Case for a Quiet Historical Overwrite

Civilizations don’t always collapse with explosions and monuments toppling. Sometimes they dissolve through paperwork, renamed concepts, and smoother stories. Tartaria isn’t a lost empire [read more...]

“A problem cannot be solved by the same consciousness that created it.” – Albert Einstein

“A problem cannot be solved by the same consciousness that created it.” - Albert Einstein

Tartaria: What the Maps Remember

History likes to pretend it has perfect recall, but old maps keep whispering otherwise. Somewhere between the ink stains and the borderlines, a ghost [read more...]