Money Backed by Land Worked in Early America

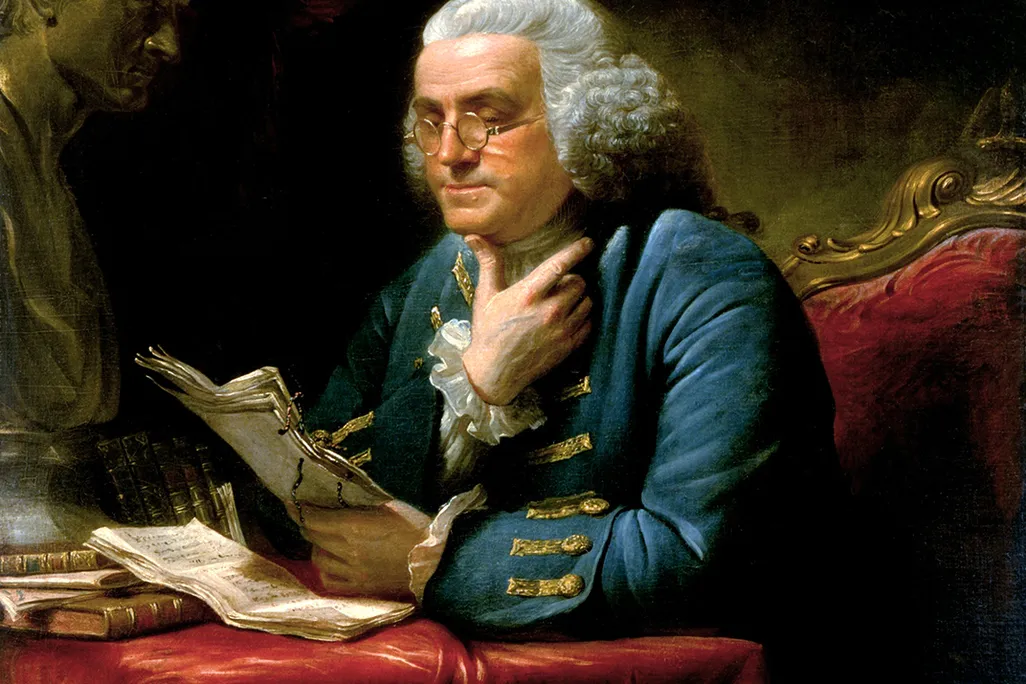

Benjamin Franklin sailed to England expecting refinement, empire, and order. Instead, he found streets crowded with beggars, economic superstition, and a society blaming workers for existing. What he saw—and how the colonies avoided that collapse—still echoes in debates about money and prosperity today.

Benjamin Franklin witnessed widespread poverty in London and decided to do things differently in Philadelphia

The Empire of Beggars

Franklin landed in England shocked: the richest nation on Earth had streets packed with beggars, tramps, and unemployed workers. He couldn’t fathom how a country so wealthy could leave its laboring class destitute, and locals offered a grim explanation: “Too many people.” Some elites even treated wars and plagues as population-control tools. Franklin contrasted this with the colonies, where poorhouses sat empty, farms were full, and labor shortages—not surpluses—defined the economy. The difference wasn’t morality. It was monetary policy.

England had wealth but left workers destitute. The colonies did the opposite with smart money policy. #Neurodope #History #Economics share this

Early American marketplace bustling with trade

The Secret Ingredient: Colonial Scrip

When asked why the working class in the colonies prospered, Franklin answered simply: the colonies issued their own money. “Colonial Scrip” was distributed in proportion to goods and labor circulating in the economy. No central bank, no foreign creditors, no artificial scarcity. By matching money supply to actual economic activity, the system created a self-reinforcing loop of wages, trade, and consumption. Prosperity wasn’t luck—it was arithmetic applied to human life.

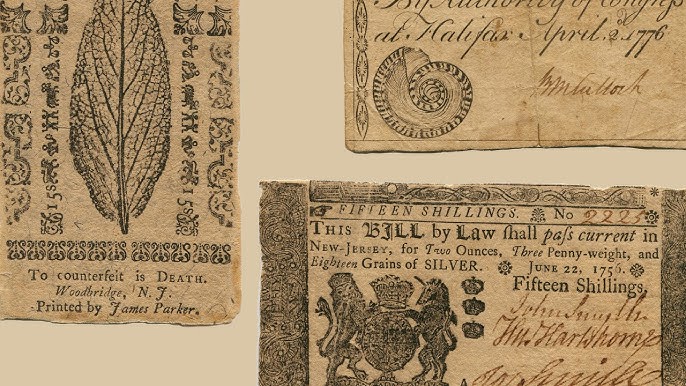

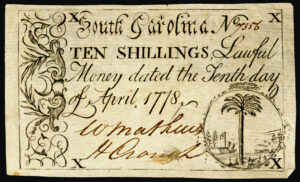

Colonial Scrip notes issued in early America

“That is simple. In the Colonies, we issue our own paper money. It is called ‘Colonial Scrip.’ We issue it in proper proportion to make the goods and pass easily from the producers to the consumers. In this manner, creating ourselves our own paper money, we control its purchasing power and we have no interest to pay to no one.” – Benjamin Franklin

Example of Colonial Scrip paper currency

Colonial Scrip matched money supply to real economic activity. Prosperity wasn’t luck—it was math. #Neurodope #Money #ColonialAmerica share this

The Pamphlet That Explained Everything

In A Modest Enquiry into the Nature and Necessity of a Paper Currency, Franklin made a sharp observation: without local currency, the colonies weren’t bartering out of virtue—they were bartering because gold and silver were drained to England. Cash-starved provinces don’t become morally superior—they become economically crippled. Barter increases costs, suppresses wages, chokes investment, and deters immigrants. Franklin’s solution: print enough paper money to facilitate internal trade, tied not to gold, not to silver, but to the actual velocity of goods and labor.

Cash-starved economies don’t thrive. Franklin solved it with paper money tied to real trade. #Neurodope #Money #Franklin share this

A colonial land bank ledger and property records map

“Coined Land” and the Stabilizing Trick

Franklin proposed a radical idea: back paper money with land, not metal. Land is stable; gold and silver are not. A properly run land bank automatically regulates money supply. If cash is scarce, people borrow against land, expanding liquidity. If cash is too abundant and losing value, it’s used to pay off mortgages, pulling money out of circulation. The economy breathes, self-corrects, and sustains trade, wages, and investment. Franklin wasn’t inventing magic. He was engineering a feedback loop.

Franklin’s land-backed money created a self-correcting economy. Not magic, just feedback. #Neurodope #Economics #ColonialMoney share this

Franklin’s accounts of English poverty and colonial prosperity mix firsthand observation with economic theory. His core argument—that colonies thrived because they controlled their own money supply—is documented in A Modest Enquiry into the Nature and Necessity of a Paper Currency (1729) and his letters in the Yale Papers of Benjamin Franklin. Some anecdotes, like the “streets of beggars” story, derive from secondary sources, but his economic reasoning on specie scarcity, barter inefficiencies, and land-backed credit is historically verified. The broader context reflects documented colonial monetary shortages and how locally issued paper money stabilized trade, wages, and growth.

Franklin’s currency system worked because it matched money supply to real economic activity. #Neurodope #Money #Revolution share this

Sidebar

Franklin, Benjamin. A Modest Enquiry into the Nature and Necessity of a Paper Currency (1729)

The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, Yale University Press

Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Colonial Currency Collection

Exploring the known and the unknown with a beat writer’s eye for truth. –Chip Von Gunten

A quick overview of the topics covered in this article.

Latest articles

Puppy Farms: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly of Dog Rescue

Puppy farms. The name alone sounds like something out of a Pixar spinoff — fuzzy optimism in pastel colors. But peel back the chew [read more...]

Dragons are Real: Folklore or Hidden Reality?

Dragons weren’t just the fever dreams of medieval artists—they left traces, hints, and echoes throughout history, from bones misidentified as giants to elaborate engravings [read more...]

Space Tourism: A Billionaire Party Above the Sky

A Neurodope Magazine look at commercial spaceflight, billionaire ego, and societal priorities in the new space race. Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, Richard Branson—are these [read more...]