Historical Anatomy – Old Hand Drawn Science Art

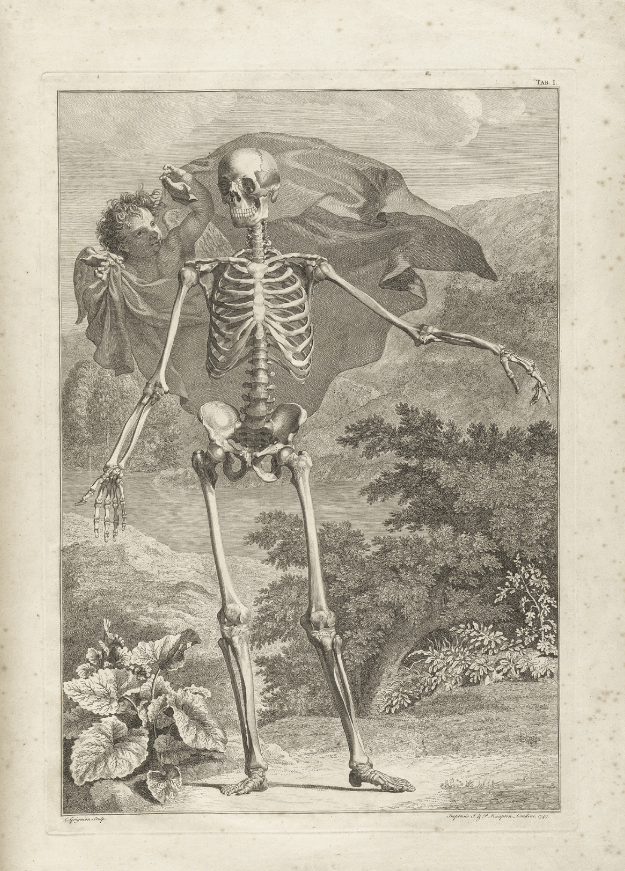

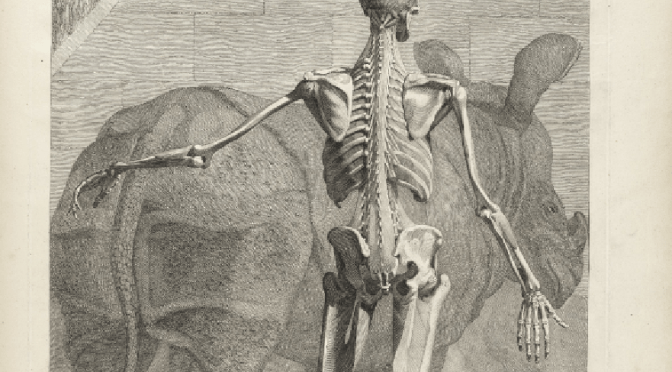

The National Library of Medicine keeps an outstanding historical record of historic studies in the human anatomy. Here is a publication from the year 1747 by Bernhard Siegfried Albinus entitled “Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani.” An English translation of the text of Tabulae was published in London in 1749 under the title, Tables of the skeleton and muscles of the human body.

Check out this slideshow:

- Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani.

- Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani.

- Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani.

- Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani.

- Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani.

- Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani.

- Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani.

- Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani.

- Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani.

- Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani.

Albinus, Bernhard Siegfried. Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani. (Londini : Typis H. Woodfall, impensis Johannis et Pauli Knapton, 1749).

Bernhard Siegfried Albinus (i.e. Weiss) was born in Frankfurt an der Oder on February 24, 1697, the son of the physician Bernhard Albinus (1653-1721). He studied in Leyden with such notable medical men as Herman Boerhaave, Johann Jacob Rau, and Govard Bidloo and received further training in Paris. He returned to Leyden in 1721 to teach surgery and anatomy and soon became one of the most well-known anatomists of the eighteenth century. He was especially famous for his studies of bones and muscles and his attempts at improving the accuracy of anatomical illustration. Among his publications were Historia muscolorum hominis (Leyden, 1734), Icones ossium foetus humani (Leyden, 1737), and new editions of the works of Bartholomeo Eustachio and Andreas Vesalius. Bernhard Siegfried Albinus died in Leyden on September 9, 1770.

Bernhard Siegfried Albinus is perhaps best known for his monumental Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani, which was published in Leyden in 1747, largely at his own expense. The artist and engraver with whom Albinus did nearly all of his work was Jan Wandelaar (1690-1759). In an attempt to increase the scientific accuracy of anatomical illustration, Albinus and Wandelaar devised a new technique of placing nets with square webbing at specified intervals between the artist and the anatomical specimen and copying the images using the grid patterns. Tabulae was highly criticized by such engravers as Petrus Camper, especially for the whimsical backgrounds added to many of the pieces by Wandelaar, but Albinus staunchly defended Wandelaar and his work.

Source: National Library of Medicine

A quick overview of the topics covered in this article.

How do ya like my little magazine? Neurodope Magazine is a sardonic, science-meets-philosophy publication that explores the strange, the curious, and the mind-bending corners of reality with wit, skepticism, and insight.

If this kind of brain static hits your frequency, subscribe for articles to your inbox. I try to look deeper into things and write about them: commentary on society, science, and space.. After all, there's a whole lot of unknown unknowns out there.. and I'm curious to the ideas surrounding them. Thanks for reading! - Chip

Latest articles

Did Hitler live to old age in Argentina?

What if the concluding scene for Adolf Hitler wasn’t a poison-pilled bunker but a beach house in Argentina? In the book, Hitler’s Exile by [read more...]

Addicted to Certainty: Why Our Brains Love Dogma

Addiction to Certainty has been with us since the first brain learned to recognize a pattern in fire, in predators, in the seasons. Our [read more...]

Puppy Farms: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly of Dog Rescue

Puppy farms. The name alone sounds like something out of a Pixar spinoff — fuzzy optimism in pastel colors. But peel back the chew [read more...]