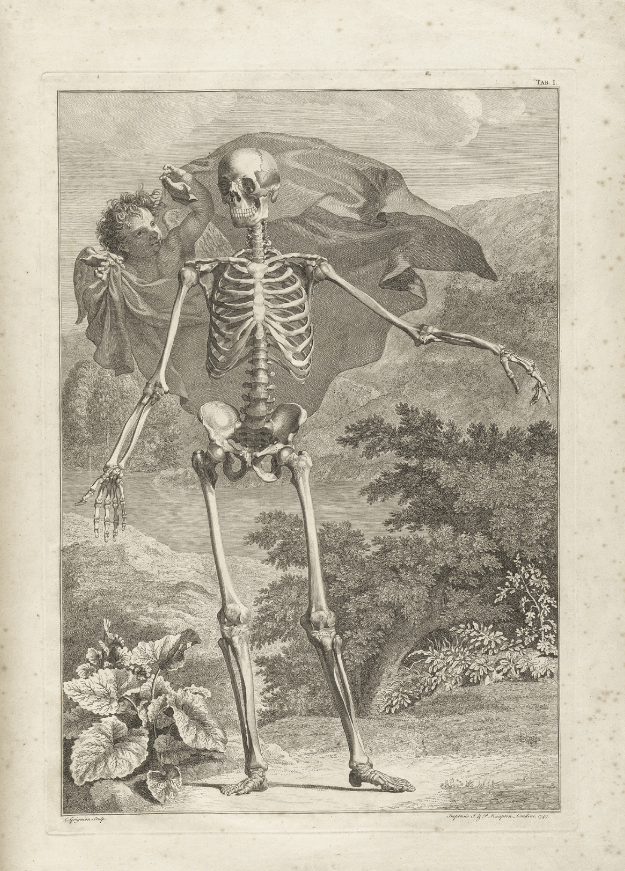

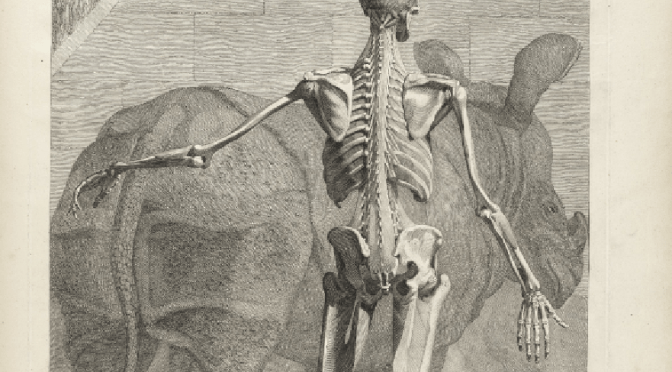

Historical Anatomy – Old Hand Drawn Science Art

The National Library of Medicine keeps an outstanding historical record of historic studies in the human anatomy. Here is a publication from the year 1747 by Bernhard Siegfried Albinus entitled “Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani.” An English translation of the text of Tabulae was published in London in 1749 under the title, Tables of the skeleton and muscles of the human body.

Check out this slideshow:

- Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani.

- Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani.

- Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani.

- Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani.

- Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani.

- Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani.

- Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani.

- Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani.

- Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani.

- Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani.

Albinus, Bernhard Siegfried. Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani. (Londini : Typis H. Woodfall, impensis Johannis et Pauli Knapton, 1749).

Bernhard Siegfried Albinus (i.e. Weiss) was born in Frankfurt an der Oder on February 24, 1697, the son of the physician Bernhard Albinus (1653-1721). He studied in Leyden with such notable medical men as Herman Boerhaave, Johann Jacob Rau, and Govard Bidloo and received further training in Paris. He returned to Leyden in 1721 to teach surgery and anatomy and soon became one of the most well-known anatomists of the eighteenth century. He was especially famous for his studies of bones and muscles and his attempts at improving the accuracy of anatomical illustration. Among his publications were Historia muscolorum hominis (Leyden, 1734), Icones ossium foetus humani (Leyden, 1737), and new editions of the works of Bartholomeo Eustachio and Andreas Vesalius. Bernhard Siegfried Albinus died in Leyden on September 9, 1770.

Bernhard Siegfried Albinus is perhaps best known for his monumental Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani, which was published in Leyden in 1747, largely at his own expense. The artist and engraver with whom Albinus did nearly all of his work was Jan Wandelaar (1690-1759). In an attempt to increase the scientific accuracy of anatomical illustration, Albinus and Wandelaar devised a new technique of placing nets with square webbing at specified intervals between the artist and the anatomical specimen and copying the images using the grid patterns. Tabulae was highly criticized by such engravers as Petrus Camper, especially for the whimsical backgrounds added to many of the pieces by Wandelaar, but Albinus staunchly defended Wandelaar and his work.

Source: National Library of Medicine

A quick overview of the topics covered in this article.

Latest articles

The Cognitive Rent Economy: How Every App Is Leasing Your Attention Back to You

You don’t lose your attention anymore. You lease it. Modern platforms don’t steal focus. They monetize it, slice it into intervals, and return it [read more...]

AI Is an Opinionated Mirror: What Artificial Intelligence Thinks Consciousness Is

Artificial intelligence thinks it sees us clearly. It does not. It is staring into a funhouse mirror we built out of math, bias, hunger [read more...]

The Age of the Aeronauts: Early Ballon flights

Humans have always wanted to rise above the ground and watch the world shrink beneath them without paying a boarding fee or following traffic [read more...]

Free Energy from the Ether – from Egypt to Tesla

Humans have always chased power from the invisible. From the temples of Egypt to Tesla’s lab in Colorado, inventors sought energy not trapped in [read more...]

The Philosophy of Fake Reality: When Simulation Theory Meets Neuroscience

What if reality isn’t breaking down—but revealing its compression algorithm? Neuroscience doesn’t prove we live in a simulation, but does it show the brain [read more...]

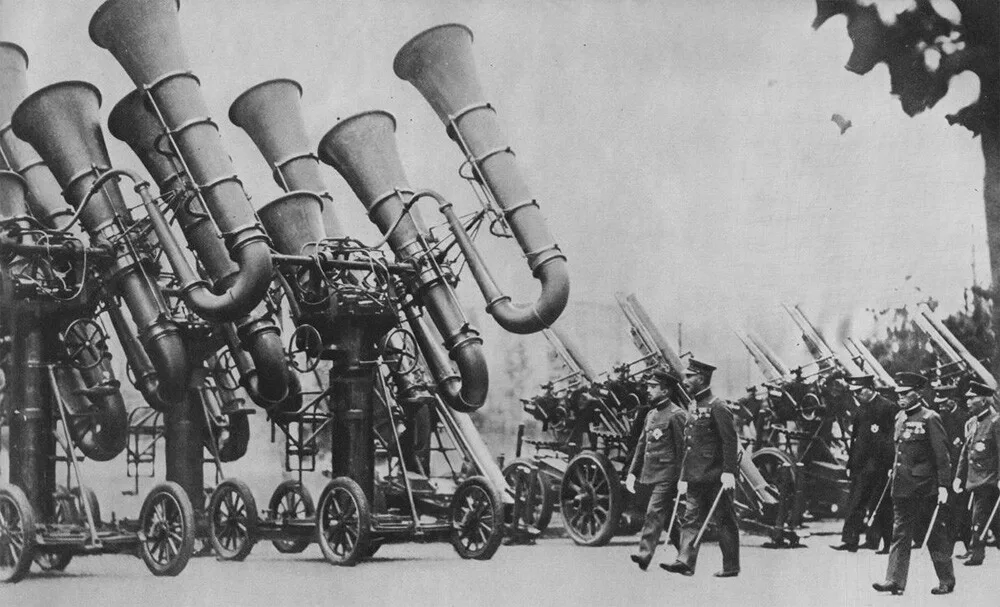

Blast from the Past: Exploring War Tubas – The Sound Locators of Yesteryears

When it comes to innovation in warfare, we often think of advanced technologies like radar, drones, and stealth bombers. However, there was a time [read more...]

Pneumatic Tube Trains – a Lost Antiquitech

Before electrified rails and billion-dollar transit fantasies, cities flirted with a quieter idea: sealed tunnels, air pressure, and human cargo. Pneumatic tube trains weren’t [read more...]

Tartaria and the Soft Reset: The Case for a Quiet Historical Overwrite

Civilizations don’t always collapse with explosions and monuments toppling. Sometimes they dissolve through paperwork, renamed concepts, and smoother stories. Tartaria isn’t a lost empire [read more...]

“A problem cannot be solved by the same consciousness that created it.” – Albert Einstein

“A problem cannot be solved by the same consciousness that created it.” - Albert Einstein

Tartaria: What the Maps Remember

History likes to pretend it has perfect recall, but old maps keep whispering otherwise. Somewhere between the ink stains and the borderlines, a ghost [read more...]