A Bizarre Instance Surrounding Genetics is the Story of Henrietta Lacks

One of the most bizarre instances surrounding the study of genetics and genomics is the story of Henrietta Lacks. In 1951, Lacks, a 31-year-old African American woman, was diagnosed with cervical cancer. Without her knowledge or consent, doctors at Johns Hopkins Hospital took a biopsy of her cancerous cells.

This 1940s photo made available by the family shows Henrietta Lacks. In 1951, a doctor in Baltimore removed cancerous cells from Lacks without her knowledge or consent. Those cells eventually helped lead to a multitude of medical treatments and formed the groundwork for the multibillion-dollar biotech industry.

These cells, which were later named HeLa cells after Lacks, turned out to be the first immortal human cell line that could grow indefinitely in a laboratory.

Those cells turned out to be immortal. Not metaphorically. Literally. They reproduced endlessly in lab conditions, defying normal cellular death, and became the backbone of modern biology. They helped create the polio vaccine, fueled cancer research, and shaped how we understand genetics and virology. Her microscopic immortality built empires of knowledge, but Henrietta’s family didn’t even know it was happening until two decades later.

The entire biomedical ecosystem thrives on access to human tissue. The vaccines in your arm, the drugs in your cabinet, the treatments that save lives—they all started with someone’s cells. The moral tangle begins when the body becomes both contributor and commodity, and when anonymity is treated as ethical absolution. We delete your name, keep your DNA, and call it progress.

The entire biomedical ecosystem thrives on access to human tissue. The vaccines in your arm, the drugs in your cabinet, the treatments that save lives—they all started with someone’s cells. The moral tangle begins when the body becomes both contributor and commodity, and when anonymity is treated as ethical absolution. We delete your name, keep your DNA, and call it progress.

Behind every Petri dish, there’s a pulse.

Henrietta’s cells weren’t just a miracle of replication—they were a story of erasure and rediscovery. Her name had been lost in the machinery of scientific detachment until her family fought to reclaim it. And when they did, the question lingered like formaldehyde in the air: who owns the flesh once it leaves the body?

The HeLa legacy is still alive—literally, in labs across the globe—but it also changed the cultural code of biomedical ethics. It forced institutions to reconsider how they treat the origin of their specimens. Consent forms got longer. Disclaimers got denser. And yet, the quiet exchange continues: tissue for knowledge, anonymity for progress.

So next time you sign that clipboard at the doctor’s office, think about it. Your body is a story. Sometimes it ends with a bandage. Sometimes it ends in a freezer, dividing endlessly under a microscope, helping to save lives you’ll never meet.

It's not cool to steal human cells without consent. Share on X

Though Lacks died in 1951, HeLa cells were and still are used in labs around the world. They were used for the discovery of the polio vaccine, chemotherapy, gene mapping, and in vitro fertilization, among other medical breakthroughs. (Researchers still haven’t figured out why they’re “immortal,” but they’ve since discovered other similarly inextinguishable cell lines.)

Today, the story of Henrietta Lacks is still being told through books, films, and articles, bringing attention to the importance of ethical considerations in scientific research. Do you think the taking of cells from a person without consent is ethical?

A quick overview of the topics covered in this article.

Latest articles

The Cognitive Rent Economy: How Every App Is Leasing Your Attention Back to You

You don’t lose your attention anymore. You lease it. Modern platforms don’t steal focus. They monetize it, slice it into intervals, and return it [read more...]

AI Is an Opinionated Mirror: What Artificial Intelligence Thinks Consciousness Is

Artificial intelligence thinks it sees us clearly. It does not. It is staring into a funhouse mirror we built out of math, bias, hunger [read more...]

The Age of the Aeronauts: Early Ballon flights

Humans have always wanted to rise above the ground and watch the world shrink beneath them without paying a boarding fee or following traffic [read more...]

Free Energy from the Ether – from Egypt to Tesla

Humans have always chased power from the invisible. From the temples of Egypt to Tesla’s lab in Colorado, inventors sought energy not trapped in [read more...]

The Philosophy of Fake Reality: When Simulation Theory Meets Neuroscience

What if reality isn’t breaking down—but revealing its compression algorithm? Neuroscience doesn’t prove we live in a simulation, but does it show the brain [read more...]

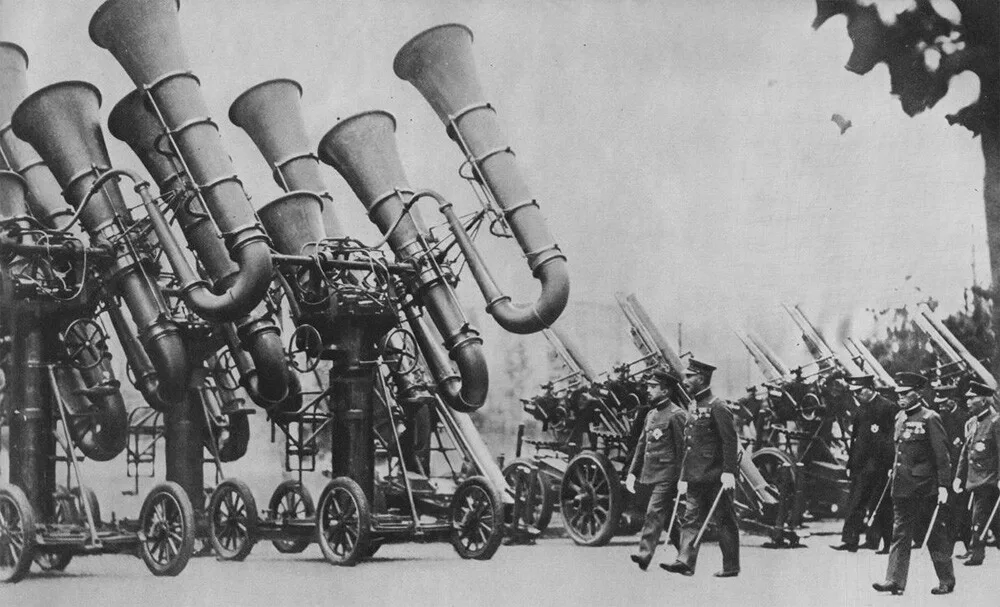

Blast from the Past: Exploring War Tubas – The Sound Locators of Yesteryears

When it comes to innovation in warfare, we often think of advanced technologies like radar, drones, and stealth bombers. However, there was a time [read more...]

Pneumatic Tube Trains – a Lost Antiquitech

Before electrified rails and billion-dollar transit fantasies, cities flirted with a quieter idea: sealed tunnels, air pressure, and human cargo. Pneumatic tube trains weren’t [read more...]

Tartaria and the Soft Reset: The Case for a Quiet Historical Overwrite

Civilizations don’t always collapse with explosions and monuments toppling. Sometimes they dissolve through paperwork, renamed concepts, and smoother stories. Tartaria isn’t a lost empire [read more...]

“A problem cannot be solved by the same consciousness that created it.” – Albert Einstein

“A problem cannot be solved by the same consciousness that created it.” - Albert Einstein

Tartaria: What the Maps Remember

History likes to pretend it has perfect recall, but old maps keep whispering otherwise. Somewhere between the ink stains and the borderlines, a ghost [read more...]