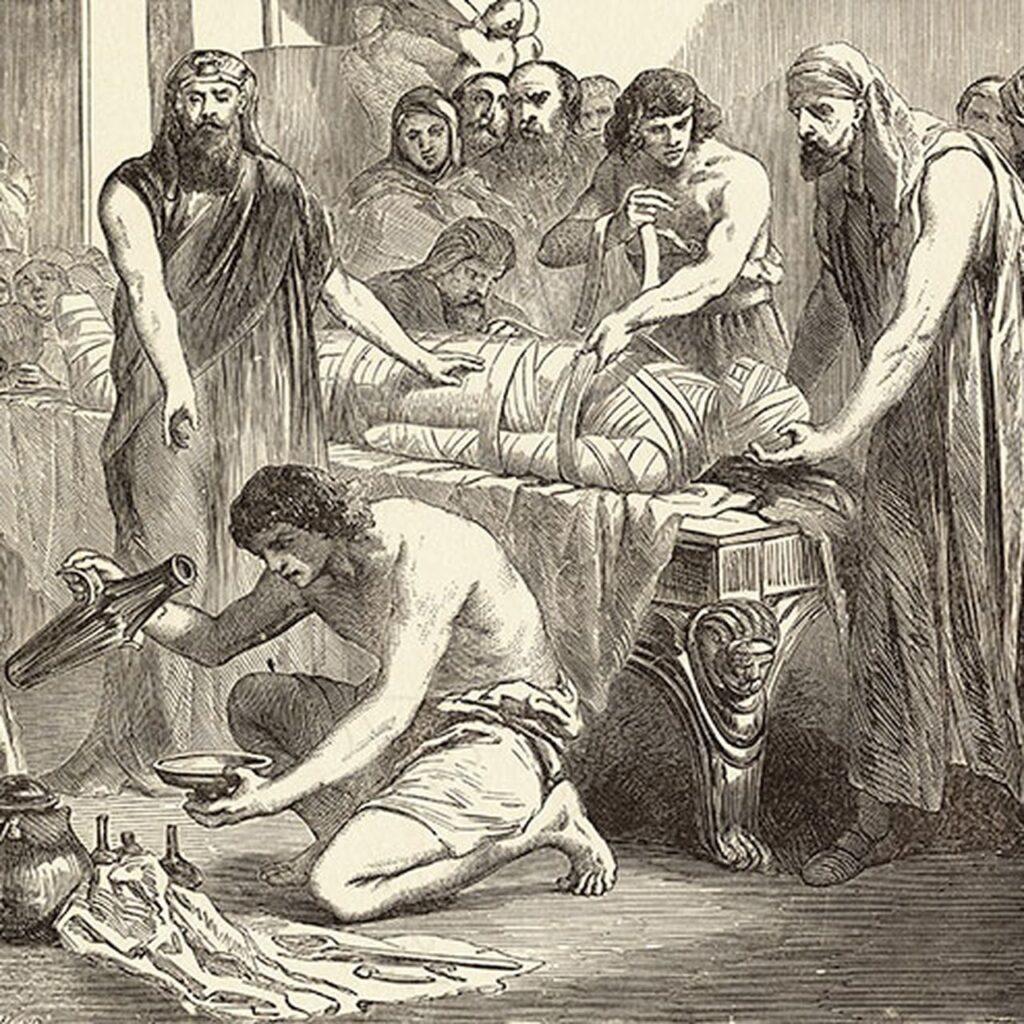

The Mummy Industrial Complex: When the Dead Became a Commodity

Exploring the known and the unknown with a beat writer’s eye for truth. -Chip Von Gunten

A quick overview of the topics covered in this article.

Latest articles

Nietzsche Was an Arrogant Nihilist

Philosophers love to argue that human reason is either a cosmic accident or a cosmic inheritance. Nietzsche bet on accident. The older minds—Plato, Socrates—bet [read more...]

“Science is the great antidote to the poison of enthusiasm and superstition.” – Adam Smith

"Science is the great antidote to the poison of enthusiasm and superstition." - Adam Smith

“In a time of deceit telling the truth is a revolutionary act.” – George Orwell

"In a time of deceit telling the truth is a revolutionary act." - George Orwell