A New Orleans Cult Favorite Musician

Professor Longhair wasn’t just another blues man hammering at the keys—he was a cosmic glitch in the matrix of American music, a trickster saint from Bogalusa who taught a busted piano how to dance. Born Henry Roeland Byrd in 1918, better known as Roy “Bald Head” Byrd or simply “Fess,” he didn’t come from the conservatory side of the street. He was a street hustler first, a survivor, a rhythm merchant selling the tempo of the city before he ever sold a song. Somewhere in his thirties, when the piano became his hustle instead of dice or cards, he sat down at a keyboard missing teeth and turned the handicap into his fingerprint. Out of that broken symmetry came a sound that didn’t fit any template—syncopated, syncopated again, then flipped over and syncopated sideways until your brain forgot how four-four worked.

New Orleans didn’t just give birth to jazz—it raised a whole litter of strange geniuses who made rhythm feel humid and alive. In 1948, Fess found himself at the Caldonia Club, and owner Mike Tessitore took one look at that wild hair and christened him “Professor Longhair,” because he played like a man who didn’t just study music but rewrote the damn syllabus. The band he led was called the Shuffling Hungarians, a name so mysterious it might’ve been a private joke between God and the bayou. His first recordings came a year later, for a tiny Dallas label called Star Talent. One track, “Mardi Gras in New Orleans,” opened with a whistled intro that sounded like a man conjuring ghosts through his teeth. The union squabbles of the time killed the release, but Mercury picked him up later that year and Fess started leaving fingerprints across American sound forever.

The 1950s saw him hustling his way through Atlantic, Federal, and a handful of scrappy New Orleans labels. He had one national hit—“Bald Head”—credited to Roy Byrd & His Blues Jumpers, but commercial success was never the point. He wrote songs like “Tipitina,” “Big Chief,” and “Go to the Mardi Gras” that still feel like secret codes to the soul of the Crescent City. Journalist Tony Russell once said Longhair’s sound was “too weird to sell millions.” He wasn’t wrong. The rhumba rhythms, the choked laughter in his singing, the left-hand shuffle that sounded like the Mississippi rolling through Havana—it wasn’t made for the charts. It was made for the alleyways, the parades, the after-hours joints that smelled like sweat, gin, and trumpet spit.

But Fess became something more than a hitmaker—he became a gravitational field. You can hear him echoing through Allen Toussaint, Dr. John, and every New Orleans piano bar that still believes rhythm is a form of rebellion. He had two great eras: first, the dawn of rhythm and blues; later, the resurrection, when the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival dug his ghost out of history and gave him back to the living.

Professor Longhair died in 1980, but every Mardi Gras still starts with that whistle, that shuffle, that sly grin inside the groove. His piano didn’t just play music—it reminded people that joy itself can be syncopated, improvised, and a little bit broken.

Exploring the known and the unknown with a beat writer’s eye for truth. -Chip Von Gunten

A quick overview of the topics covered in this article.

Latest articles

“In a time of deceit telling the truth is a revolutionary act.” – George Orwell

"In a time of deceit telling the truth is a revolutionary act." - George Orwell

“A problem cannot be solved by the same consciousness that created it.” – Albert Einstein

“A problem cannot be solved by the same consciousness that created it.” - Albert Einstein

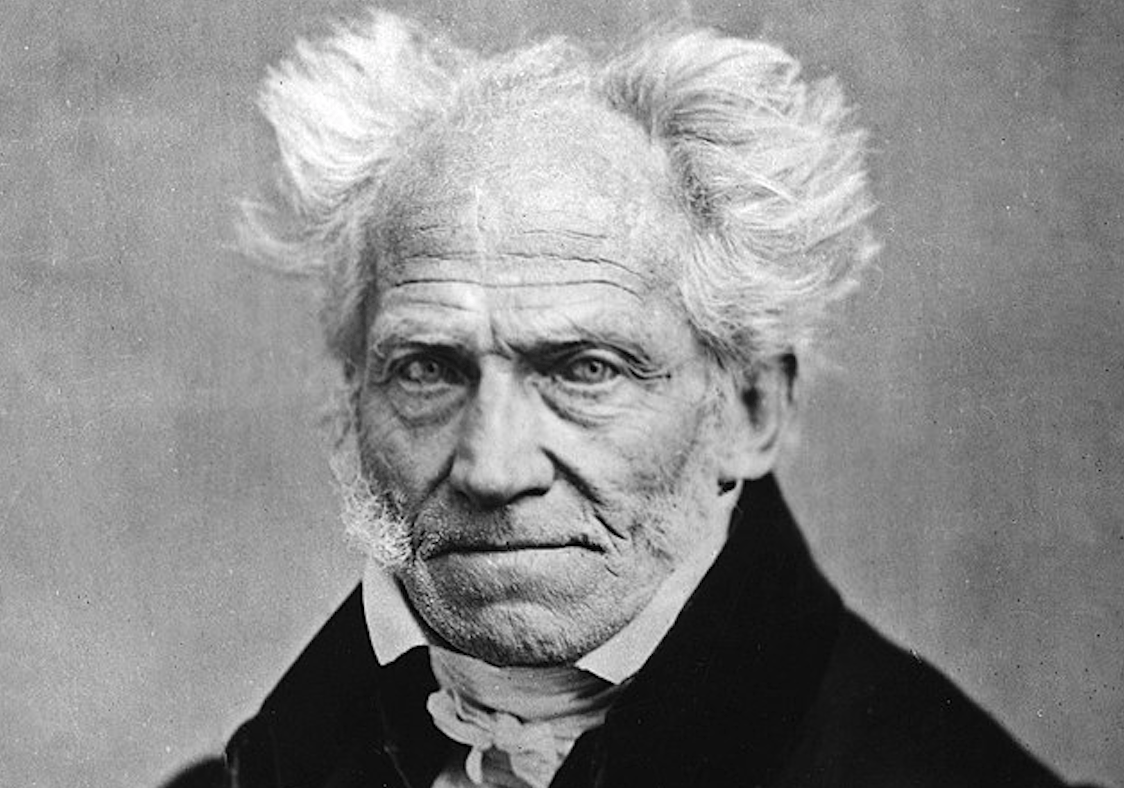

“All truth passes through three stages. First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as being self-evident.” – Arthur Schopenhauer

"All truth passes through three stages. First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as being self-evident." - [read more...]